Revising Your Novel—And Building a Revision System That Works for You 🖋️📚

I am not a published author (yet 🤞). I am honored to share some techniques from what I've learned these past fourteen years of writing, revising, and querying my novels.

I wrote 13 novels before I sold Elantris, which was my sixth. The big change for me happened when I managed to figure out how to revise.

— Brandon Sanderson, How Did You Get Published?

Up until three years ago—I sucked at revision. I would go as far as to say I didn’t know the first thing about it.

When friends would tell me, “Yeah Luke, I’m working on the fifth draft of my novel.”

I’d be like, “Oh yeah sure,” *cough* *cough*, “I work on my novel, too.” And I did work on it.

But revision is not a sheer act of will (although, it takes bravery). It is a learned skill. I’ve spent the last three years dedicating time, research and practice to become a “student of revision.”

Thinking Like An Engineer.

When I am not writing novels, I work as a software engineer and app developer, and I love systems that work.

I find the problem-solving process of strategizing and swarming the issue exhilarating. I love when, on a team, creative ideas start to manifest like popcorn. Novel writing is so much like building a complex software system.

To write a novel effectively, it takes testing, refactoring (a fancy word for rewriting/revising), and designing. And ultimately, it takes a team of people (more on that later with beta readers!).

In my time studying revision, I stumbled upon a system that works for me. It’s not only stimulated my growth as a writer, but has enabled me to effectively revise my novels.

Ultimately, it’s caused the stories I write to get better, and has improved how readers have received them. This system has enabled me to blast through more than 10+ revisions in the last two years (while still doing normal life stuff, like raising kiddos with my amazing wife and holding down a fairly demanding job).

For the sake of this article, I am assuming you are “along for the ride” as far as your novel takes you, and that your journey may end with pursuing publishing.

With that in mind, let’s get started!

First Draft Highs.

I’ll never forget how excited I was when I finished the first draft of my 57,000 word young adult urban fantasy novel in November of 2010.

I had sometimes dreamed of writing a novel, and had even outlined some ideas and written test chapters, but it took a kick in the pants from a friend to finally do it. She believed in me and constantly reminded me that I could do it.

Finishing that draft was amazing. I felt like I had unlocked a new superpower. I could write freaking novels now. I loved writing.

But, I knew my book wasn’t great, yet. And in my opinion, a lot of it wasn’t even all good (some of it was, but we’ll get back to that later).

So I started reading up on how to “revise” my novel—or whatever that was supposed to mean.

Second Draft Blues, and Burn Out.

I researched editing and revision. Namely, I read some books, scoured blog posts, and listened to vague explanations of the editing process from wildly successful authors. My thoughts around the subject kind of went to mush.

Until finally, I sat down at the keyboard and stared at the document.

And I tried.

I kept myself busy rewriting paragraphs, adding words, removing commas, etc.

Then, I replaced a few words, here and there. I was scared to death to delete anything. So, I would delete a paragraph and then put it back.

I added some nice themes and imagery throughout the whole thing.

I wondered if first person point-of-view was too edgy, so I switched it to third person.

Then, I switched it back to first person.

And then…

I gave up on that project. I didn’t know how to finish it, so I didn’t.

Moving On?

Instead, I actually worked on four more books, resulting in: two completed first drafts for two other novels, one zero draft (I share Alexa Donne’s definition) for another novel, and one partially completed first draft for a fourth novel.

That was, until I had the realization. A real “come to Jesus” moment.

I decided my ‘answer’ wasn’t in starting the next book. It would be in learning to finish something… Speaking of which.

💡 As a reminder, please make sure to make peace with what “finish” means to you.

Note: That could mean, printing it, giving it a kiss, putting a blanket on it, and/or burning it with fire.

A System for Revision.

(Before you go on —

I’d like to preface this section with this: I don’t think my system is the best one, nor the only one, it’s just what’s worked for me so far.

Also, to the best of my ability, I’ve attached the resources that I gleaned from on this topic at the bottom of this article. Some are pretty broad—so, hopefully this system can help give you some practical tips that help you get more value out of those.)

This is the system of revision I developed that has worked for me:

Read your book as a reader.

Solicit reader feedback.

Experience/read your book as an editor.

Create a revision outline.

Implement the revision.

Rinse and repeat.

1. Read Your Book as a Reader

The goal of this time is to take off the writer hat (or editor hat) experience your book as a reader. Encountering it differently will reveal things in the draft you’ve never noticed before.

Time Estimate: 1-2 weeks

You need to READ your book… as if it’s a book you just checked out from the library.

I can’t emphasize this enough.

👏 Get. 👏 Out. 👏 Of. 👏 That. 👏 Doc (or Scrivener, Ulysses, Evernote, etc.).

More than anything else, I highly recommend listening to the book in this stage. I find it really helps produce the right mindset shift from writer to reader. I use Speechify to read the entire contents of my novel (I just paste it in). I have spent hundreds of hours using this.

If you tried listening and hate it (if you haven’t yet, try it!)... you could go to a site (like Kindle Direct Publishing) and pay a small amount to print a “Proof Copy” of your book.

Be extremely careful here. Don’t let this site distract you. Don’t add any cover. No editing. Nope. Just print and pay. Burn the book later.

Seriously, you’ll just waste your time. And you’ll get stuck in nitpick mode.

You will need to get into that mindset soon… But right now, you need to just try and read… and enjoy… and hate… some parts of your book.

If something comes up, throw it in a note to be aggregated later. (More on this in 3 & 4).

2. Solicit Reader Feedback

The goal of this time is to learn about what is working and not working with your book. If you invest in this early, you can quickly identify if your promises are paying off. Later in the journey, it can help guide final edits.

Time Estimate: 4-6 weeks (can be started concurrently before finishing the first step)

Beta Readers

Beta readers can be your friends, significant other, children, or even coworkers! There are even paid services for beta readers available out there.

Discerning people help you get a sense of issues early on.

This feedback…

Tells you what’s working, and what’s not working

Helps solidify promises & payoffs.

Help you know when you are headed in the wrong (or right) direction.

I find getting beta reader feedback especially helpful in the earliest and the latest drafts of my book.

I recommend not being afraid to send out the first draft to readers! (We call this “alpha” testing in the software world.) Plan to test about the first ¼ of your novel or so (I recommend not much more than Act One)—which is arguably the shortest act in your novel (Ref, How to Outline Your Novel with Save the Cat!).

I use Google Forms to gather this feedback. Here’s an example survey I send with each chapter.

Toward the end of your revisions, send the whole book out again.

Here’s an example survey I sent out for the entire book (In this round, I only surveyed readers once at the end).

Not all feedback is beneficial. Expect to throw out, or to have to translate the “real” meaning of the feedback of 25-75% of it.

Writing Groups

Going through your book with a writing critique group can also be incredibly helpful. I am so grateful for the groups I have been (and still am) a part of.

I’ve found the best groups are ones where you submit regularly. Make sure you plan out how many weeks it will take to get through your novel to see if it meets your goal.

💡 I’ve had friends even get plugged into these online through writer membership organizations (i.e., small groups that email one other their work every week). However, I do not have one I can personally recommend. If you have any you have used and recommend, I’d love to hear them!

3. Review Your Book as an Editor

The goal of this time is to burn a ton of brain calories, thinking critically about your plot, your setting, and your characters. Studying “story” can be helpful here. Here are two strategies I employ. For more information, check out some of the resources below under “On Story & Plotting”.

Time Estimate: 1-3 weeks (start this with the others ongoing, but incorporate feedback from 2 before closing this out)

Strategy One: Read & Brainstorm

Read your book again, but this time the goal is to look it over analytically.

💡 One tip for this is to pretend you are giving feedback on a friend’s book, or tell yourself that you are a literary agent reading this for the first time. Be kind, but don’t forget to think critically (critical ≠ negative).

As I listen to the book, I use Siri to write notes. Later on, I’ll aggregate those into a document.

This is the time to figure out the key “problems”/edits in the book. Summarize and prioritize your thoughts on what you think is wrong or broken in the book. I’ve heard Brandon Sanderson refer to this as a bug fix punch list (this speaks to me as an engineer).

This list become the source data for your revision plan!

Strategy Two: The “Show Doctor”

Musical theater legends tell stories of producers bringing in a “show doctor” to help them improve a production that is struggling with test audiences or critics. Stories go that they’ll often point out specific beats or moments in the show that need to change, and the team will solve the problem by inserting a fantastic musical or dance number. “The show must go on!”

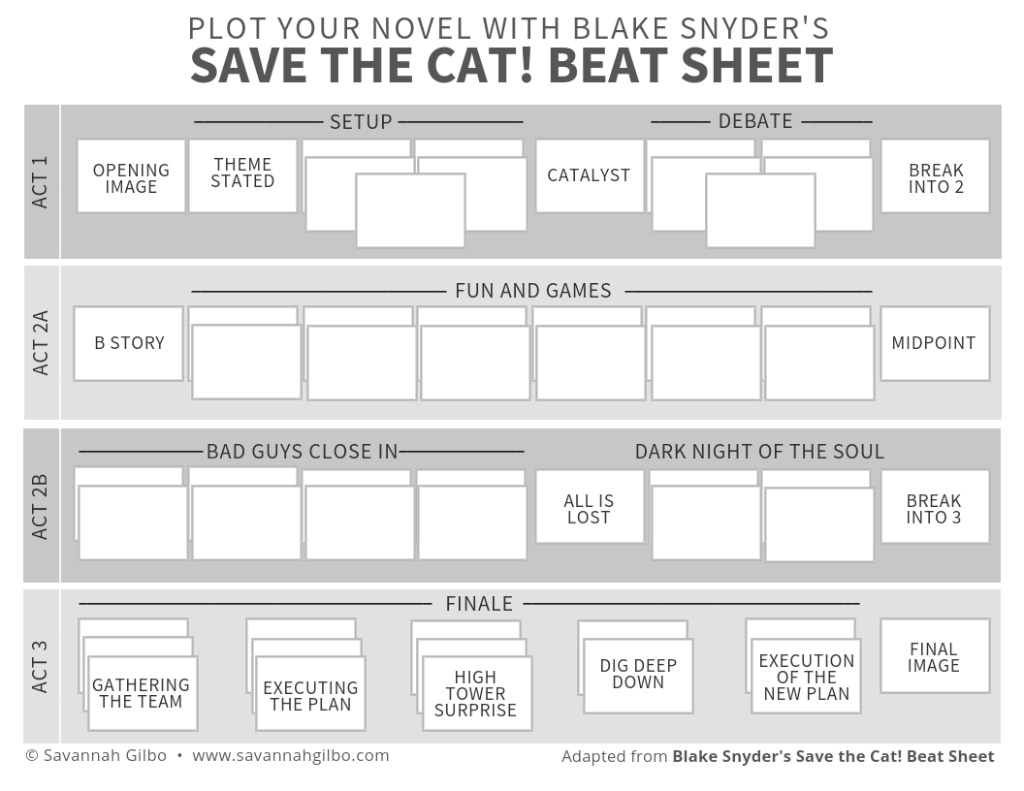

I have found this can be done with novels, as well! Whether you are a pantser or a plotter, you can benefit from this strategy. Here’s how to do it using Blake Snyder’s “13 Beat Sheet” to diagnose problems in your story:

Write your “Three Act Description - Today.” I recommend writing this in a document and keep it to about one page long (one paragraph per act works well), making sure to hit the points on the beat sheet. If a few things are missing, that’s great. You’re potentially exposing something. Do the best you can. And remember, don’t write it as you want the story to be, but as it is!

Write “Three Act Description - Proposed.” Again, keep it to about a page long. The goal here is to write it as you think it could be. Try two or three options. Don’t sacrifice your story or the hook… But also, don’t be afraid to go a little wild! Write options that you never dreamed of. Lean into the beats. The goal is to learn something or try something in a very low-risk low-cost way.

Pitch the new options to some friends… Get curious and ask why certain ideas intrigued them. You may already have an opinion on which is better.

In this you may discover:

You have the wrong “bad guy.”

Your hook is not strong enough.

There are more possible layers that would increase conflict and tension.

You are missing a B-Story (or letting one fall flat).

And more!

(Fun fact, all of these happened to me!)

4. Create a Revision Plan

This is basically a list of problems/edits with your book. I use two incredibly simple, yet useful tools for this: type & scope.

Give each problem/edit a fun name. Make sure you jot down enough context on each problem/edit that you could get started on fixing it.

Organize problems/edits into three categories: Blocking, Talking and Rocking (a definition on that in a second!).

Organize problems/edits into the following scopes:

Book-level

Chapter-level

Scene-level

Prioritize each of those categories from most-important problems within each level (so, most important book-level to least important book-level, etc.)

Time Estimate: 1-3 days (can be done concurrently)

Categorizing Revisions

I stole this idea from my time in the software engineering world reviewing code and projects (specifically, from some great leaders I worked for).

It has been incredibly helpful, and as I’ve shared it with other writers, they’ve shared this system is useful for them.

Here’s what each category means. These are strict rules! Most likely, you will have fewer Blocking problems/edits and more Rocking problems/edits. If you have too many Blocking problems/edits, you may be considering things “Blockers” that are just stylistic preferences!

Blocking means you cannot ship the book with this in there.

i.e., Your timeline is unintentionally very off; You kill off a character and bring them back because you realized you needed them (and they didn’t get raised from the dead!); Your book was originally about vampires and werewolves, then you changed it to something unique (this may or may not have been me 😉).

Talking is a question that should be answered.

i.e., “Why doesn’t the protagonist feel sorrow at their mom’s death?”; “They had the magical artifact to fix the problem in Act One. Why didn’t anyone suggest they do something about it?”; “Why did Augusta’s character disappear in Act Two and never come back or get referenced again?”.

Rocking is something that would be nice to do, but your book is still totally fine to ship without it.

i.e., You want to add more spiciness in the romance between the two main characters; You see a need for more beauty and imagery (maybe calling back to the theme) throughout the book; a minor character is falling flat.

Here’s a shortened example of my revision plan:

Example: Revision Plan

Book-Level Edits

Blocking Edit - The Timeline Edit:

Right now, the timeline doesn’t make any sense. The seasons are not consistent.

Rocking Edit - The “Beauty” Edit:

I want to really beautify the prose, especially at the high points & beats of the Acts, and at the beginning and end of chapters.

I want to call back to the theme, and hint at the progression of the characters in their journeys.

Chapter-Level Edits

Chapter 1

Rocking Edit - Fix “Mom” Interactions.

Their interactions feel fake. I want the reader to better understand their dynamics.

Scene-Level Edits

Men-in-black scene.

Blocking Edit - Cut the stupid thing! But make sure the scenes before and after flow so it still works.

Before you leave this section, review the four steps at the top of this section!

5. (Finally) Implement the Revision.

This is where the rubber hits the road. I have endeavored on revisions that have taken me upwards of twelve months.

Time Estimate: 1 week - 6 months*

*The timeline here greatly depends on the nature of the revision (or rewrite), and how focused you can keep it.

This is the section with the least amount here because… Well, this is where it’s time to take a deep breath, roll up your sleeves, and really dig into that revision!

I highly encourage you to keep the revision as focused as possible. I have had some revisions only take me a few days, and some take close to a year.

Remember, focus on Blocking, Book-Level problems/edits at first.

If you’re overwhelmed by that, start with some simple Blocking, chapter-level or scene-level edits. See if you can finish those in 1-3 hours.

These will give you confidence to tackle a book-level edit!

6. Rinse. And Repeat!

It’s time to read the book as a reader… again!

Then go back through, adjust your revision plan, and finish it.

When Am I Done Revising?

If you’re pursuing traditional publishing and don’t have a literary agent yet, the goal of the revision process is most likely to get your book ready for an agent to represent it. From what I’ve learned from

this means (my words summarizing hours of great podcasts, not theirs!):The concept is right. This includes the story and the hook. It should be unique, compelling, and leave the reader wanting more.

The writing has a strong voice.

The character arcs, pacing, and plot are well-executed and leave the reader feeling satisfied.

Thank you!

I hope that this resource can be both a template and an encouragement as you build out your own revision system. Please feel free to take it, and make it your own!

I’d love to hear from you if you find this helpful, and or what other revision processes work for you. I love to improve and iterate, so if anything here needs revision—let me know in the comments.

Additional Resources:

A. On Story & Plotting

Save the Cat! by Blake Snyder (and the wildly helpful Save the Cat! Writes a Novel by Jessica Brody).

Brandon Sanderson’s 2020 Creative Writing Lectures (especially the earlier lectures)

B. On Revision & Writing Craft

Studying the techniques of your favorite authors. Specifically, listen to author interviews and take notes.

Listening to all of Writing Excuses.

Watching professional YA novel editors on YouTube and taking notes (this was mostly unhelpful until much later in my process, since my initial revisions were more basic or fixing fundamental story issues).

C. On Defining the “Queryable” Revision For Your Book

Podcasts by

(specifically the fantastic ‘Books with Hooks’ section).Videos by

.